|

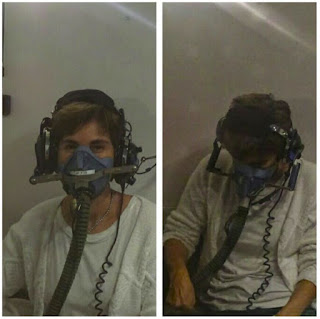

| Instructor Ron Diedrichs with EVA cadets |

Nearly a decade ago, air

safety officials in Greece suggested that that all airline pilots undergo

hypoxia training, following the loss of a Boeing 737 on a flight from

Cyprus to Athens that killed 121 people on August 14, 2005.

Neither the captain nor the first officer on Helios Flight

522 understood that the airliner was not pressurizing after takeoff from Larnaca, nor did they comprehend the meaning of the warning horn that triggered

when the cabin altitude passed 14,000 feet. For this reason, the men did not put

on their masks or descend to a lower altitude. 13 minutes after takeoff, both

pilots were unconscious and the plane continued on auto pilot until running out

of fuel and crashing near Athens.

|

| Wreckage of Helios 522 near Athens Greek AAIASB photo |

Loss of pressurization in high altitude air transport is no black swan event according to Jim Stabile Jr. of Aeronautical Data Systems. He's been crunching the numbers and has found that rapid de-pressurization incidents occur at a rate of from once a week (using numbers from Australia and New Zealand) and de-pressurization events of all kind happen even more frequently.

Ten years ago, the Greeks investigating the Helios disaster

were concerned that the debilitating effects of oxygen deprivation were not appreciated

by many pilots, creating an air safety risk. Military aviators undergo regular sessions in

altitude chambers where they experience what it feels like to be in the

oxygen-thin air at flight levels where they will be flying. This familiarity

with the symptoms of the onset of hypoxia help them respond in a timely manner

if they should ever find themselves in an unpressurized airplane. The Greeks wondered, would civilian pilots

benefit from hypoxia testing?

The NASA anonymous reporting system, which

encompasses all decompression, shows "an average rate of 1 every 3 days," Stabile told me.

The practice of “chamber flights” is not without its detractors. Because it is, by its nature, staged and highly controlled, with operators standing by ready to press a mask onto the face of wobbly participants, pilots may believe the situation is manageable. Mitch Garber an aerospace physician formerly with the National Transportation Safety Board says hypoxia training that relies on giving pilots a chamber experience so they can then self-identify is akin to relying on people who drink to say they are too drunk to drive.

“You’re in no shape to judge with hypoxia,” he told me.

Since a healthy chunk of Lost and Confounded details my theory

of pilot incapacitation by hypoxia on MH-370, I thought it important to experience

altitude sickness myself. This is how I happened to be in a classroom with two

dozen EVA Airline student pilots in the Arizona State University’s high altitude chamber last week.

Now that it is over, I can say Dr. Garber is correct on one

front. Nothing about a contrived experience, intended to protect our health as

well as give us mild oxygen starvation is comparable to what it must have been

like on the MH-370 flight deck on March 8, 2014.

First, the Malaysia Airlines

Boeing 777 was flying at 35,000 feet - significantly higher in real distance

and speed of hypoxia onset than the testing chamber at 25,000 feet. Second, those pilots didn’t know it was

coming. We did.

|

| Facts and figure before the chamber flight |

|

| EVA cadets work on math problems at 25,000 feet |

Across from me, some of the young Taiwanese pilots were also

scribbling answers but others were just looking around grinning. (Luis) Shih-Chieh Lu

told me he felt like he was drunk. While (Josh) Yuchuan Chen said - with some disappointment - that he

really hadn’t felt too different.

While I was hoping for the euphoria, giddiness and feeling

of well-being that gives hypoxia the nickname, “the happy death” when the

shortage of oxygen did start to affect me, my symptoms did not meet my

expectation. It was a totally unpleasant experience. I felt nauseous, blackness in my peripheral vision,

out of breath and very, very flush. After

about one minute, my breathing was labored. My head lolling started after about

2 minutes in.

After two and a half minutes, all I could do was muster

enough energy to push the talk button on my microphone and complain, “Hot” to

the folks outside the box controlling the air conditioning. That was it for me because the next thing I knew I woke up

with an oxygen mask on and worried faces were turned in my direction. I’d

been out for about half a minute.

|

| Before and after 2.5 minutes at 25K |

Many of the students said they also anticipated more

drama in the chamber but Dr. Garner

insists this training is not about experiencing drama, happy or otherwise and

it isn’t about seeing how long one can remain off mask. It is about learning to

recognizing the individual early warning signs of oxygen deprivation so those

in command of airliners can act fast and act right.

“Hopefully they remember their symptoms, what

were the really big keys for them, that’s what you want,” Garner said. After a few days thinking about it, Yuchuan told me that was his take-away.

|

| Garner (R), Diedrich and Gayla Marsh supervise the chamber |

When the safety hazard is an invisible thief of capable of

stealing a pilot’s ability to be alarmed, pilots need to know in advance to be

very afraid.

No comments:

Post a Comment